Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, The Schrödinger Equation, and Particle in a Box

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle

The uncertainty principle tells us that there is a limit to how well we can measure the position and momentum of a particle.

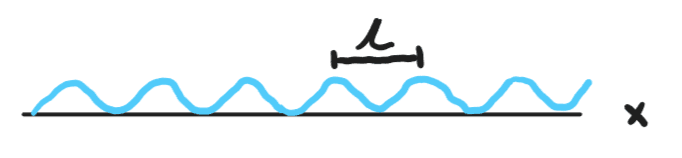

Suppose that we have a wave defined by a known wavelength:

\psi(x) = Asin(2\pi x/\lambda)

Note that by knowing the wavelength of the particle, we can interpret the momentum of the particle by the de Broglie equation:

p = h/\lambda

Shown above is our wavefunction for a known wavelength. However, as you can see knowing the wavelength leaves some uncertainty when it comes to knowing the position of the particle across the x-axis.

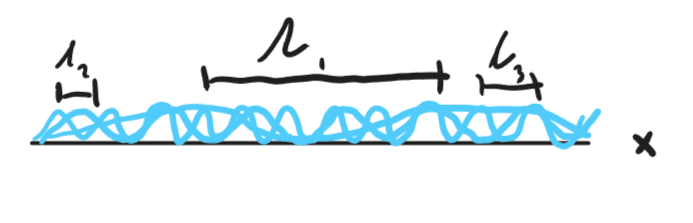

Now lets imagine we don’t know the wavelength of the wavefunction. We can imagine this as the superposition of many different wave frequencies.

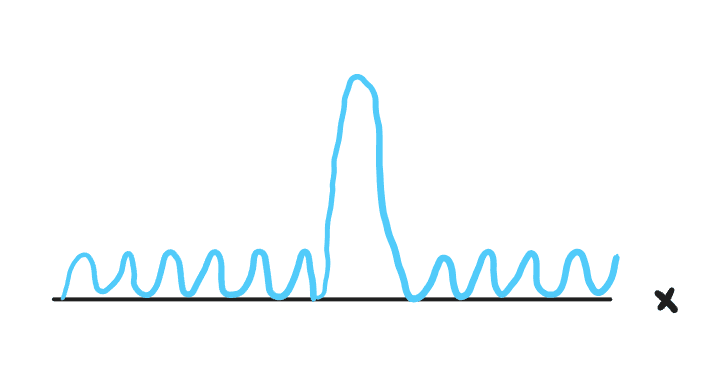

Although it may look messy, the sum of these waves can actually produce the following:

We can see that now in this case, we have a clear indication of the particles position, but an unclear indication of the particels wavelength and thus momentum.

This limit to how well we can know the position and the momentum of a particle at the same time is given by the Heisenberg Uncertaintiy Principle and is modeled by the following equation:

Quantum Mechanics in Atoms: Shrodinger Equation

To describe the energy of electrons in an atom we can use the Schrödinger Equation.

The one-dimensional time-independent Schrodinger Equation can be described by the following equation:

-\frac{\hbar^2}{2m} \frac{d^2 \psi(x)}{dx^2} + V(x)\psi(x) = E \psi(x)It describes how the wavefunction \psi(x), which represents the quantum state of a particle of mass m, behaves under the influence of a potential energy function V(x). In this equation, -\frac{\hbar^2}{2m}\frac{d^2}{dx^2} represents the kinetic energy operator, V(x)\psi(x) represents the potential energy contribution, and E is the total allowed energy of the system.

Note that this equation is quantized and therefore there are only certain allowable energy states.

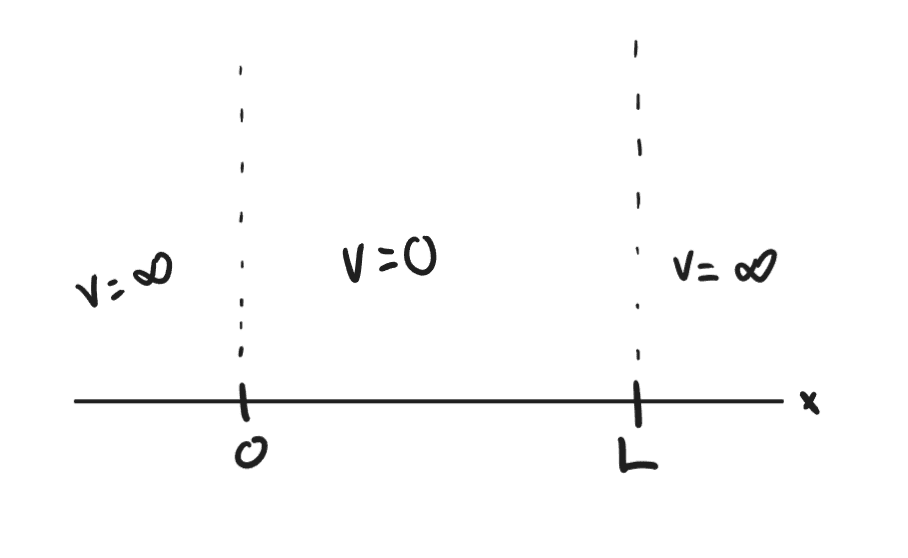

Particle in a Box

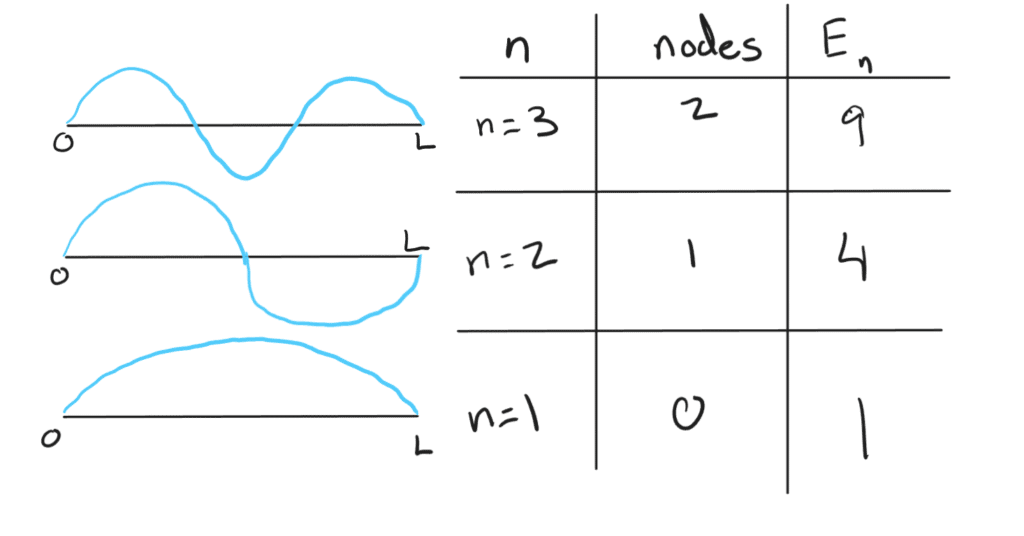

Lets assume that we have a particle in one-dimension along the x-axis where we have labeled points along this axis of 0 and L. Lets say that inside of 0 and L, the V = 0 and that outside of 0 and L on both sides, the V = infinity. Therefore the particle is trapped in between points 0 and L. The point of this experiment is to gain intuition on the energy and position of the particle using Schrodinger’s equation.

To obtain the wavefunction, we can make an educated guess that:

\psi(x) = A \sin(kx) + B \cos(kx)To solve this equation we must now determine the boundary conditions. We know from looking at standing waves that the wavefunction for the particle must be 0 at the ends of the functions and therefore:

\psi(0) = 0,

\psi(L) = 0At x = 0:

\psi(0) = A \sin(0) + B \cos(0) = B = 0Therefore:

\psi(x) = A \sin(kx)At x = L

\psi(L) = A \sin(kL) = 0This requires that:

kL = n\pi, \quad n = 1, 2, 3, \dotsWe have now seen that our B coefficient = 0, and our k coefficient = k = n\pi/L. However, we still need to solve for our A term. For this we can use normalization of the integral of probability.

When we take the square of the wave function, it can be interpreted as the intensity or probability of finding a particle at that x and therefore, we know that the area under the curve of the wave function squared from 0 to L must equal 1. Lets do the math:

\int_0^L |\psi(x)|^2 dx = 1\int_0^L A^2 \sin^2!\left(\frac{n\pi x}{L}\right) dx = 1A = \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}}And now we can recover that A = \sqrt{(2/L)}. Plugging everything in:

\psi(x) = \sqrt{(2/L)}\sin(n\pi x/L)Now lets plug in the wavefunction into our Schrödinger equation to solve for our allowed energies. Remember that V = 0 and thus we are solving for KE. Doing the math, you will find that:

E_n = h^2n^2/8mL^2We often call these discrete energy values “eigenvalues”

n = 0 is not allowed because then our wavefunction will reduce to 0 and thus there will be no probability of finding the particle anywhere, and no particle at all. A consequence of this is that there is always some energy where n = 1. This is called the zero-point energy.

Absorption and Emission Spectra

How do particles transition between different energy states? Electronic transitions are when electrons move from higher or lower energy states to new energy states and thus releasing or absorbing a photon. Absorption of a photon will increase the energy state of an electron and emission of a photon will decrease the energy state of an electron.

If we were to take white light and shine it on a system, and then break down the light into a spectrum, we will see that all wavelengths of the spectrum are shown, except for the discrete wavelengths where that energy is absorbed to transition energy states. In contrast, when electrons move down energy states they will release discrete wavelengths of energy.

This principle is the basis for spectroscopy.

The difference in energy can be given by \Delta E = hv because hv is the energy of a photon.

Note that convention is that when \Delta E is positive, it represents absorption and when \Delta E is negative it represents emission.

Fundamentals of Quantum Chemistry

Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, The Schrödinger Equation, and Particle in a Box Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle The…

Defining a Function – Python

Functions in Python: Definition, Examples, and Best Practices What is a Function in Python? A…